School days

Young Billy Bishop grew up in the inland port city of Owen Sound on Georgian Bay, touted to be "the next Liverpool". He was distinguished from the other children on several counts. He spoke with a slight lisp. Also, he was the only boy in town who attended classes at Miss Pearl's Dancing School with the local girls. Add to that, his mother sent him to school in suit and tie; his schoolboy classmates scorned his formal dress and damaged his garb. Then too, he did not care for team sports like lacrosse, football, and hockey, preferring solitary sports, such as riding, swimming, or billiards at the YMCA or local pool halls. Most especially, he became a marksman. His father gave him a .22 caliber rifle for Christmas, along with a promise of 25 cents for every squirrel the youth shot. The family orchard, which had been overrun by a destructive plague of squirrels, was soon free of the beasts as the young sniper mastered the one-shot kill. Some sources insist that the young hunter learned the art of deflection shooting, the knack of leading a moving target, at this time.

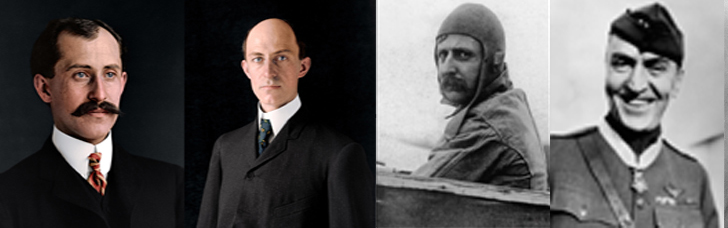

Defending himself against teasing, Bishop earned the reputation of a fighter on the schoolyard, defending himself and others easily against bullies. Once, he fought seven boys, and won. And if he drew male antagonism, he had no problem attracting female company. He was slender and of average height, but undeniably handsome, with a firm jaw, full lips, and straight nose over a pencil moustache.

In the classroom, it was a different tale. Bishop was less successful at his studies; he would abandon any subject he could not easily master, and was often absent from class. In 1910, at the age of 16, after reading a newspaper article, Bishop built a glider out of cardboard, wooden crates, bedsheets, and twine, and made an attempt to fly off the roof of his three-story house. He was dug, unharmed, out of the wreckage by his sister Louise. After she helped him hide the wreckage, she insisted he owed her a favor, and insisted he date her girlfriend Margaret Burden.

The granddaughter of Timothy Eaton, the department store magnate, Margaret Burden became friends with Louise Bishop during summer vacations to Owen Sound. Once she met Billy, they were smitten with one another, which greatly annoyed her parents.

College

On his 17th birthday, 8 February 1911, Billy Bishop applied to the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) in Kingston, Ontario, where his brother Worth had graduated in 1903. Bishop placed 42nd of the 43 candidates admitted to the three-year school. He spent a hard first year during 1911 and 1912, struggling academically. He also suffered severe hazing from seniors; RMC regulations barred him from retaliatory fisticuffs. Then he was caught cheating on a year-end exam, and narrowly avoided expulsion. Too humiliated to return home for the summer, he stayed in Kingston and worked for Worth. Bishop was readmitted to the RMC as a second year student for the 1912–1913 term, though with an extra year's study added for him to graduate. That year, he raised his class standing to 23rd of 42 students.

During the 1913–1914 term, Bishop's class standing sagged to 33rd of 34. On 28 August 1914, he returned to RMC as a senior. After 15 of Bishop's classmates left school to serve as officers in the burgeoning war, Bishop withdrew from the RMC on 30 September 1914 with the same intention. That same day, he was commissioned into a cavalry unit, the Mississauga Horse. He journeyed to Toronto to inform Margaret Burden of his decision before reporting for duty.

First World War

Mud and manure

When The Mississauga Horse shipped out for the war, Second Lieutenant Bishop was not with them; he was in hospital with pneumonia and allergies. After recovering, he was transferred to the 7th Canadian Mounted Rifles, a mounted infantry unit, then stationed in London, Ontario, in January 1915. Bishop was placed in charge of the regimental machine guns. Popular with the enlisted men, Bishop was nicknamed "Bish" and "Billy". He excelled on the firing range. As one of his subordinates remembered:[14]

"Bish would just riddle a target that the rest of us could barely see. The instructors would keep putting it further back, until it was just a tiny black dot, and he'd shoot it to ribbons...he put every damn' bullet on target. He never missed."

Mishap continued to dog Bishop. On 6 April 1915, a horse he was riding reared and fell on him; he was back riding a week later. At the end of the month, the bolt of a rifle he was firing blew back and whacked him on the cheekbone. Then he became so ill from an inoculation that he fell off his horse. It was during this time that Bishop slipped away to Ontario, and proposed marriage to Margaret Burden. She accepted, and they were engaged. He gave her his RMC ring as a symbol of his troth.

Bishop's unit left Canada for England on 6 June 1915 on board the requisitioned cattle ship Caledonia as part of a convoy. The voyage through rough seas was poor on food. Most of the 240 men and 600 horses on board were seasick. From time to time, the ship's crew chucked dead horses overboard. On 21 June, near Ireland, U-boats attacked the convoy. Three ships were sunk and 300 Canadians killed, but Bishop's ship was unharmed, arriving in Plymouth harbour on 23 June.

The 7th Canadian Mounted Rifles were assigned to train at Shorncliffe Cavalry Camp. Training was in outmoded cavalry tactics. Living in tents, the Canadians suffered through sandstorms when the weather dried; usually, though, they existed in a rainy swamp of mud and horse manure. Bishop spent another spell in hospital in late July. Afterwards, during one especially mucky day, Bishop watched an aeroplane land in a nearby field. He remarked to his companion, "You don't get any mud or horseshit on you up there. If you died, it would be a clean death." Bishop decided to apply for a transfer.

Into the air

On a jaunt to London, Bishop subsequently wrangled an appointment with the Royal Flying Corps recruitment officer, Lord Hugh Cecil. When Bishop was told it would be a year before he could train as a pilot, he accepted the immediate chance to become an aerial observer. On 1 September, he reported to 21 (Training) Squadron at Netheravon for elementary air instruction. The first aircraft he trained in was the Avro 504 Having taken a month for preliminary training, on 2 October 1915 Bishop transferred to gunnery training at Dover. By the end of October, Bishop was crossing the English Channel and flying his first missions in a combat zone, directing artillery fire. On 24 November, Bishop's pilot crashed their airplane upon landing back in England. Bishop suffered a bruised foot; the pilot was also only bruised. Three days later, Bishop took a check ride in a new aircraft. When he wrote home to Margaret describing this flight, he boasted of a 300 mph (400 km) dive in an aircraft that could not have exceeded half that. Such braggadocio characterized his correspondence with her.

No. 21 Squadron was re-equipped with new Royal Aircraft Factory RE.7s. On 15 January 1916, No. 21 Squadron began its transfer to France. By 23 January, as the squadron established itself at Boisdinghem, Bishop began a three-day illness. He emerged from hospital to join his squadron in adjusting to the realities of the infant military science of aerial warfare. Until this time, fliers on both sides of the conflict had been fumbling their way towards mounting firearms on aircraft. When Bishop emerged from hospital, there were already reports of German Fokker Eindecker monoplanes that could fire a machine gun through their propeller arc without striking a blade. Aim the aircraft; aim the gun. As the deadly little Fokkers slowly multiplied on the front, they became feared by the Royal Flying Corps as the Fokker Scourge. In response, the RFC quit single plane patrols, mandating two escorts for every reconnaissance aircraft. However, casualties were rare, and dismissed airily. One of Bishop's letters to his fiancée mentioned that the German fliers were chivalrous; the two sides exchanged dropped messages on the occasional casualty. Bishop wrote: "It is awfully nice to be on such good terms with one's enemies, and everyone here speaks very highly of all the German flyers. They seem to all be of a fine crowd."

Meanwhile, No. 21 Squadron RFC was discovering that their underpowered RE.7s could not take flight with a bomb load, and so failed as a bomber. The awkward crew positioning also hindered its fighting ability, with the observer in front with a non-synchronized Lewis gun hemmed in by struts and bracing wires. The pilot was seated behind him, back under the upper wing.[29]

The rest of Bishop's time as an observer was a string of mishaps. Weather aloft was arctic bitter. A three and a half hour flight on 9 February 1916 frostbit his cheek so severely it burst open and put him back under medical care. In March, he was injured in a vehicle collision. Then he was hit in the head by an aircraft cable; he spent two days unconscious. This was followed by an abscessed tooth. Once returned to duty, he whacked a knee against an aircraft's frame when his pilot pulled a hard landing.

Bishop was then granted a three-week leave to England. As he strode down the gangplank at Folkestone on 2 May 1916, he stumbled and fell onto his sore knee. Three other soldiers behind him toppled over him to compound his injury. Resolved not to miss his holiday, Bishop limped through his leave. Just before he returned to France, he turned himself in to have his knee treated at the hospital at Bryanston Square. Once hospitalized, he was informed on 26 May that he would face a medical board to determine his further fitness for service. After Bishop awakened from a nap, he found a well-dressed elderly woman at his bedside. Lady St. Helier insisted she knew his father from a reception in Canada, and thus was a family friend. Lady St. Helier was widely known for both her wide circle of influential friends, and for her charitable tendencies. The latter attribute had brought her to the hospital. Now she used her influence to remove Bishop from hospital and install him as one of her guests in her four-story mansion, where he mingled with, and charmed, her influential social circle.

After Bishop faced a medical board, he was sent back to Canada to recuperate on home leave. In four months of aerial combat, he had not fired his machine gun at the enemy. However, he received local acclaim in Owen Sound for his service. Then too, the Burdens overcame their objections to Bishop's suit, and agreed to their daughter's official engagement. She was presented with an actual engagement ring.

Aerial combat

Bishop returned to England in September 1916, and, with the influence of St Helier, was accepted for training as a pilot at the Central Flying School at Upavon on Salisbury Plain. His first solo flight was in a Maurice Farman "Shorthorn".

In November 1916 after receiving his wings, Bishop was attached to No. 37 Squadron RFC at Stow Maries, Essex, flying the BE.2c. He was officially appointed to flying officer duties on 8 December 1916. Bishop disliked flying at night over London, searching for German airships, and he soon requested a transfer to France.

On 17 March 1917, Bishop arrived at 60 Squadron at Filescamp Farm near Arras, where he flew the Nieuport 17 fighter. At that time, the average life expectancy of a new pilot in that sector was 11 days, and German aces were shooting down British aircraft 5 to 1. Bishop's first patrol on 22 March was less than successful. He had trouble controlling his run-down aircraft, was nearly shot down by anti-aircraft fire, and became separated from his group. On 24 March, after crash-landing his aircraft during a practice flight in front of General John Higgins, Bishop was ordered to return to flight school at Upavon. Major Alan Scott, the new commander of 60 Squadron, convinced Higgins to let him stay until a replacement arrived.

The next day, Bishop claimed his first victory when his was one of four Nieuports that engaged three Albatros D.III Scouts near St Leger. Bishop shot down and mortally wounded a Lieutenant Theiller, but his engine failed in the process. Bishop landed in no man's land, 300 yards (270 m) from the German front line. After running to the Allied trenches, Bishop spent the night on the ground in a rainstorm. There Bishop wrote a letter home, starting, "I am writing this from a dugout 300 yards from our front line, after the most exciting adventure of my life."[44] General Higgins personally congratulated Bishop and rescinded his order to return to flight school.

On 30 March 1917, Bishop was named a flight commander with a temporary promotion to captain a few days later. On 31 March, he scored his second victory. Bishop, in addition to the usual patrols with his squadron comrades, soon flew many unofficial "lone-wolf" missions deep into enemy territory, with the blessing of Major Scott. As a result, his total of enemy aircraft shot down increased rapidly. On 8 April, he scored his fifth victory and became an ace. To celebrate, Bishop's mechanic painted the aircraft's nose blue, the mark of an ace. Former 60 Squadron member Captain Albert Ball, at that time the Empire's highest scoring ace, had had a red spinner fitted.

Bishop's no-holds-barred style of flying always had him "at the front of the pack," leading his pilots into battle over hostile territory. Bishop soon realized that this could eventually see him shot down; after one patrol, a mechanic counted 210 bullet holes in his aircraft. His new method of using the surprise attack proved successful; he claimed 12 aircraft in April alone, winning the Military Cross for his participation in the Battle of Vimy Ridge. The successes of Bishop and his blue-nosed aircraft were noticed by the Germans, and they began referring to him as "Hell's Handmaiden". Ernst Udet called him "the greatest English scouting ace" and one Jasta had a bounty on his head.

On 30 April, Bishop survived an encounter with Jasta 11 and Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. In May, Bishop received the Distinguished Service Order for shooting down two aircraft while being attacked by four others.

On 2 June 1917, Bishop flew a solo mission behind enemy lines to attack a German-held aerodrome, where he claimed that he shot down three aircraft that were taking off to attack him and destroyed several more on the ground. For this feat, he was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC), although it has been suggested that he may have embellished his success. His VC (awarded 30 August 1917) was one of two awarded in violation of the warrant requiring witnesses (the other being the Unknown Soldier),] and since the German records have been lost and the archived papers relating to the VC were lost as well, there is no way of confirming whether there were any witnesses. It seems to have been common practice at this time to allow Bishop to claim victories without requiring confirmation or verification from other witnesses.

In July, 60 Squadron received new Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5s, a faster and more powerful aircraft with better pilot visibility. In August 1917, Bishop passed the late Albert Ball in victories to become (temporarily) the highest scoring ace in the RFC and the third top ace of the war, behind only the Red Baron and René Fonck.

At the end of August 1917, Bishop was appointed as the Chief Instructor at the School of Aerial Gunnery and given the temporary rank of major.

Leave to Canada

Bishop returned home on leave to Canada in fall 1917, where he was acclaimed a hero and helped boost the morale of the Canadian public, who were growing tired of the war. On 17 October 1917, Bishop married his longtime fiancée, Margaret Eaton Burden. After the wedding, he was assigned to the British War Mission in Washington, D.C. to help the Americans build an air force. While stationed there, he wrote his autobiography entitled Winged Warfare.

Return to Europe

Upon his return to England in April 1918, Bishop was promoted to major and given command of No. 85 Squadron, the "Flying Foxes". This was a newly formed squadron, and Bishop was given the freedom to choose many of the pilots. The squadron was equipped with S.E.5a scout planes and left for Petit Synthe, France, on 22 May 1918. On 27 May, after familiarizing himself with the area and the opposition, Bishop took a solo flight to the Front. He downed a German observation plane in his first combat since August 1917, and followed with two more the next day. From 30 May to 1 June, Bishop downed six more aircraft, including German ace Paul Billik, bringing his score to 59 and reclaiming his top scoring ace title from James McCudden, who had claimed it while Bishop was in Canada, and he was now the leading Allied ace.

The Government of Canada was becoming increasingly worried about the effect on morale if Bishop were to be killed, so on 18 June he was ordered to return to England to help organize the new Canadian Flying Corps. Bishop was not pleased with the order coming so soon after his return to France. He wrote to his wife: "This is ever so annoying." The order specified that he was to leave France by noon on 19 June. On that morning, Bishop decided to fly one last solo patrol. In just 15 minutes of combat, he added another five victories to his total. He claimed to have downed two Pfalz D.IIIa scout planes, caused another two to collide with each other, and shot down a German reconnaissance aircraft.

On 5 August, Bishop was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and was given the post of "Officer Commanding-designate of the Canadian Air Force Section of the General Staff, Headquarters Overseas Military Forces of Canada." He was on board a ship returning from a reporting visit to Canada when news of the armistice arrived. Bishop was discharged from the Canadian Expeditionary Force on 31 December and returned to Canada.[62]

By the end of the war, he had claimed some 72 air victories, including two balloons, 52 and two shared "destroyed" with 16 "out of control". Historians including Hugh Halliday and Brereton Greenhous (both of whom were official historians for the Royal Canadian Air Force) suggested that the actual total was far lower. Brereton Greenhous felt the actual total of enemy aircraft destroyed was only 27.--Wikipedia