James Smith "Mac" McDonnell (April 9, 1899 – August 22, 1980) was an American aviator, engineer, and businessman. He was an aviation pioneer and founder of McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, later McDonnell Douglas, and the James S. McDonnell Foundation.

Early life

Born in Denver, Colorado, McDonnell was raised in Little Rock, Arkansas, and graduated from Little Rock High School in 1917. He was a graduate of Princeton University class of 1921, and earned a Master's of Science in Aeronautical Engineering from MIT in 1925. While attending MIT he joined the Delta Upsilon fraternity. After graduating from MIT, he was hired by Tom Towle for the Stout Metal Airplane Division of the Ford Motor Company. In 1927, he was hired by the Hamilton Metalplane Company to develop similar metal monoplanes. He then went on to Huff Daland Airplane Company.

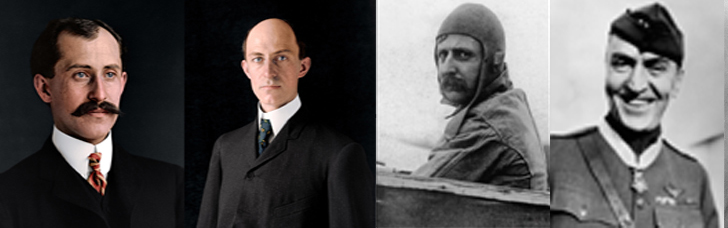

John Knudsen Northrop (November 10, 1895 – February 18, 1981) was an American aircraft industrialist and designer who founded the Northrop Corporation in 1939.

His career began in 1916 as a draftsman for Loughead Aircraft Manufacturing Company (founded 1912). He joined the Douglas Aircraft Company in 1923, where in time he became a project engineer. In 1927 he joined the Lockheed Corporation, where he was a chief engineer on the Lockheed Vega transport. He left in 1929 to found Avion Corporation, which he sold in 1930. Two years later, he founded the Northrop Corporation. This firm became a subsidiary of Douglas Aircraft in 1939, so he co-founded a second company named Northrop.

Early life and entering aviation

Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1895, Northrop grew up in Santa Barbara, California. In 1916 Northrop's first job in aviation was in working as a draftsman for the Santa Barbara-based Loughead Aircraft Manufacturing Company. After the outbreak of the First World War, Northrop was drafted into the U.S Army, where he served in the Army Signal Corps. Northrop served in the military for 6 months before Loughead successfully petitioned for his return to work in the private sector. In 1923, Northrop joined Douglas Aircraft Company, participating in the design of the Douglas Round-the-World-Cruiser and working up to project engineer.

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (23 May 1848 – 10 August 1896) was a German pioneer of aviation who became known as the "flying man". He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders, therefore making the idea of "heavier than air" a reality. Newspapers and magazines published photographs of Lilienthal gliding, favourably influencing public and scientific opinion about the possibility of flying machines becoming practical.

Lilienthal's work led to him developing the concept of the modern wing.[4][5] His flight attempts in 1891 are seen as the beginning of human flight[6] and the "Lilienthal Normalsegelapparat" is considered to be the first airplane in series production, making the Maschinenfabrik Otto Lilienthal in Berlin the first air plane production company in the world. Otto Lilienthal is often referred to as either the "father of aviation" or "father of flight".

On 9 August 1896, his glider stalled and he was unable to regain control. Falling from about 15 m (50 ft), he broke his neck and died the next day.

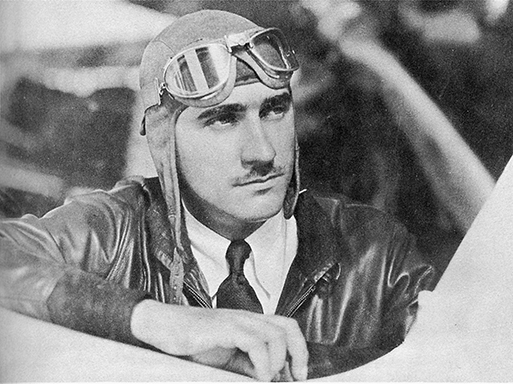

Albert Paul Mantz (August 2, 1903 – July 8, 1965) was a noted air racing pilot, movie stunt pilot and consultant from the late 1930s until his death in the mid-1960s. He gained fame on two stages: Hollywood and in air races.

Early years

Mantz (the name he used throughout his life) was born in Alameda, California, the son of a school principal, and was raised in nearby Redwood City, California. He developed his interest in flying at an early age; as a young boy, his first flight on fabricated canvas wings was aborted when his mother stopped him as he tried to launch off the branch of a tree in his yard. In 1915, at age 12, he attended the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco and witnessed the world-famous Lincoln Beachey make his first ever flight in his new monoplane, the Lincoln Beachey Special.

Richard "Dick" Ira Bong (September 24, 1920 – August 6, 1945) was a United States Army Air Forces major and Medal of Honor recipient in World War II. He was one of the most decorated American fighter pilots and the country's top flying ace in the war, credited with shooting down 40 Japanese aircraft, all with the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter. He died in California while testing a Lockheed P-80 jet fighter shortly before the war ended. Bong was posthumously inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1986 and has several commemorative monuments named in his honor around the world, including an airport, two bridges, a theater, a veterans historical center, a recreation area, a neighborhood terrace, and several avenues and streets, including the street leading to the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Saburō Sakai (坂井 三郎, Sakai Saburō, 25 August 1916 – 22 September 2000) was a Japanese naval aviator and flying ace ("Gekitsui-O", 撃墜王) of the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. Sakai had 28–64 aerial victories, including shared ones, according to official Japanese records, but his autobiography, Samurai!, which was co-written by Martin Caidin and Fred Saito, claims 64 aerial victories.

Early life

Saburō Sakai was born on 25 August 1916 in Saga Prefecture, Japan. He was born into a family with an immediate affiliation to the samurai and their warrior legacies. Their ancestors were themselves samurai and had taken part in the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598) but were later forced to take up a livelihood of farming after haihan-chiken in 1871. He was the third-born of four sons (his given name literally means "third son") and had three sisters. Sakai was 11 when his father died, which left his mother alone to raise seven children. With limited resources, Sakai was adopted by his maternal uncle, who financed his education in a Tokyo high school. However, Sakai failed to do well in his studies and was sent back to Saga after his second year.

Captain Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, OM, CBE, AFC, RDI, FRAeS (27 July 1882 – 21 May 1965) was an English aviation pioneer and aerospace engineer. The aircraft company he founded produced the Mosquito, which has been considered the most versatile warplane ever built, and his Comet was the first jet airliner to go into production.

Early life

Born at Magdala House, Terriers, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, de Havilland was the second son of The Reverend Charles de Havilland (1854–1920) and his first wife, Alice Jeannette (née Saunders; 1854–1911).[1] He was educated at Nuneaton Grammar School, St Edward's School, Oxford and the Crystal Palace School of Engineering (from 1900 to 1903).

Upon graduating from engineering training, de Havilland pursued a career in automotive engineering, building cars and motorcycles. He took an apprenticeship with engine manufacturers Willans & Robinson of Rugby, after which he worked as a draughtsman for The Wolseley Tool and Motor Car Company Limited in Birmingham, a job from which he resigned after a year.

The Wright brothers, Orville Wright (August 19, 1871 – January 30, 1948) and Wilbur Wright (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912), were American aviation pioneers generally credited with inventing, building, and flying the world's first successful motor-operated airplane. They made the first controlled, sustained flight of a powered, heavier-than-air aircraft with the Wright Flyer on December 17, 1903, 4 mi (6 km) south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, at what is now known as Kill Devil Hills. The brothers were also the first to invent aircraft controls that made fixed-wing powered flight possible.

In 1904–1905, the Wright brothers developed their flying machine to make longer-running and more aerodynamic flights with the Wright Flyer II, followed by the first truly practical fixed-wing aircraft, the Wright Flyer III. The brothers' breakthrough was their creation of a three-axis control system, which enabled the pilot to steer the aircraft effectively and to maintain its equilibrium. This method remains standard on fixed-wing aircraft of all kinds. From the beginning of their aeronautical work, Wilbur and Orville focused on developing a reliable method of pilot control as the key to solving "the flying problem". This approach differed significantly from other experimenters of the time who put more emphasis on developing powerful engines. Using a small home-built wind tunnel, the Wrights also collected more accurate data than any before, enabling them to design more efficient wings and propellers. Their first U.S. patent did not claim invention of a flying machine, but rather a system of aerodynamic control that manipulated a flying machine's surfaces.